Procurement governance has never been a particularly exciting topic. Given increasing compliance requirements, procurement has given and been given a host of policies and guidelines to follow. But is it enough to mitigate procurement risks and ensure compliance?

Why is process governance crucial in procurement?

Procurement impacts around 30% of a service company’s revenue and at least 50% of a manufacturing company’s revenue (Kearney).

External spend typically accounts for 30 to 70% of an organisation’s total expenditure (McKinsey).

What these stats mean is that getting procurement right can have far-reaching impact on an organisation’s operational and financial performance.

As a definition, governance in the context of procurement is the use of procedural arrangements to drive behaviour towards common goals for procurement, which include achieving:

- Legal/ethical compliance

- Value for money

- Competitive supply chain

For governance to be effective, the three components – people, processes, and systems – should work in harmony.

When having procurement policies alone is not enough

Most procurement departments have policies and guidelines around how procurement processes should run. In cases where the organisation is a government body or operates in a highly regulated industry, there are often multiple policies, codes of practice and layers of governance to observe.

However, ineffective governance may create unintended consequences. The table below presents some scenarios where a component in the governance framework could prevent procurement from meeting its objectives.

|

Policy or rule says |

Intended to encourage |

But might actually encourage |

|

There must be appropriate segregation of duties |

Minimised chances of fraud and conflict of interest |

Lengthened chains of approval, unidentifiable bottlenecks |

|

Purchases must be accompanied by three quotes |

Competition and value for money |

Quotes that are fake or clearly not intended to be competitive |

|

“Buy local” procurement policy |

Economic development in a local area |

Vendors disguising as local companies or collusion between local and non-local vendors |

|

Common-use supply arrangements are mandated |

Savings through economies of scale and existing relationships |

Vendors gaining too much power, reducing competition in the marketplace |

|

Approval for a transaction requires three signatures |

High level of oversight, thereby reducing the chance of fraud or error |

Diffusion of accountability, where each person assumes the other two will have given the matter their full attention and therefore does not check the details |

|

Requiring high-value transactions to be approved by a senior executive |

Having a high level of scrutiny over expenditure |

Senior executive approving without properly checking or delegating the task to an assistant (possibly by providing a login and password) |

|

Procurement must seek to obtain best value for money |

Achieving economic, social and environmental objectives |

The engagement of lowest cost suppliers rather than best overall value for money |

|

All relevant documents should be provided in response to a relevant audit request |

Ensuring probity in procurement |

Failure to create records, and using unauthorised email or document management systems |

|

All invoices should be paid within 30 days |

Timely payment and fair treatment for vendors |

Paying an invoice without performing due diligence on the vendor, or the goods and services supplied |

Adapted from NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) report 2018

Procurement process & governance health check

Below is a list of questions that management should go through to assess the effectiveness of their procurement governance:

- Are all procurement decisions defensible?

- Do our risk mitigation activities align with the organization’s key risks?

- Are processes and policies adhered to at all times?

- Is it possible to trace accountability?

- Do we have a single source of truth at all times?

- Do we have loopholes where information can be distorted?

- Do we have the right people approving/verifying information?

- Do we strike the right balance between thoroughness and the need for speed when dealing with external parties?

- Do we have visibility into process bottlenecks and workflows?

- Are processes optimised for efficiency, or can they be automated?

If the answer to one or more of the above questions is negative, top management should engage with the compliance/governance and procurement function to assess the procurement framework in the organisation. If necessary, steps should be taken to transform existing processes and systems to have a seamless procurement operating model that flows with the rhythm of the business.

The shift towards a hybrid procurement model

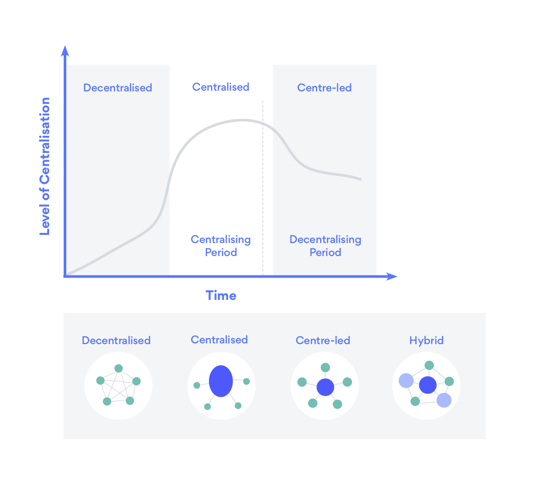

After periods of decentralising and centralising, maturing procurement organisations may find themselves heading towards the next phase of decentralisation, with many cutting-edge organisations adopting the hybrid model.

Procurement journey across different operating models. Based on KPMG research.

What is the procurement hybrid model?

Also known as "project-led, centrally enabled," this procurement operating model aims to combine the strengths of both centralised and decentralised models.

The procurement structure usually has the following attributes:

- A small to medium-sized central function responsible for coordinating company-wide procurement strategies, policies, practices and capabilities.

- The central team also segments buying categories to determine those which should be managed centrally, or those where several departments/project teams may band together under the activities of a lead department/team (i.e. lead-site buying).

- Individual departments or project teams still conduct unique/local procurement activities for their respective areas.

Why are mature organisations transitioning towards this model?

Successful implementation of the hybrid model can result in “the best of both worlds”. For instance, some expected benefits can be:

- Ensuring overarching accountability and oversight across all procurement activities – like a centralised model

- Understanding local regulatory nuances – like a decentralised model

The implications for process governance

Moving towards a decentralising period means procurement will need to serve two “masters”: end users and compliance/governance.

It’s important for procurement to maintain the balance between the needs and requirements of these two groups, which are often at opposite ends:

- Speed vs. Procedural compliance

- Ease of conducting procurement activities vs. Ensuring proper oversight by different stakeholders

- Engaging the most convenient supplier option vs. Expanding the supplier base to meet diversity quotas

Technology as an enabler for procurement process governance

Such a conundrum mentioned above is often exacerbated by using manual or inefficient systems to conduct procurement activities.

A good example in the public procurement space is governance around the sourcing of quotes. With no procurement system in place to document quoting processes, staff often raise purchase orders either without sourcing 3 quotes or receiving quotes via phone/email. When an audit is carried out, there is no way to show that the proper process was followed, and the council is hit with a non-compliance report.

The involvement of multiple stakeholders means varying levels of procurement know-how and system savviness. But the answer for procurement is not to throw a host of pre-formatted spreadsheets for various sourcing steps, accompanied by long policy documents, and hope for the best.

A procurement system for non-procurement teams

The right tool needs to accommodate procurement activities conducted by non-procurement personnel, such as operations or compliance staff.

What are some of the features that allow procurement to satisfy its two “masters”?

- Audit trail: mitigate compliance risks, ensure process transparency/accountability without onerous recordkeeping

- Automated approval and evaluation workflows: ensure accountability and efficiency while minimising procurement risks

- Comprehensive and up-to-date supplier panel arrangements: ensure compliance and value for money

- Vendor on-boarding and prequalification: user-friendly processes without sacrificing compliance

In summary

Having procurement policies and guides is as good as it gets in theory. With mature organisations transitioning towards a more decentralised procurement structure, they need to ensure their governance framework is robust enough to mitigate risks.

The right technology solution is an enabler, a facilitator, and a mediator. Before the various stakeholders know it, they will have already adhered to procurement policies by virtue of adopting technology.

---

Interested in finding out about how Felix can help your organisation strengthen procurement governance? Get in touch today!

We've released the latest edition of the Procurement Software Buyer's Guide, to help you procure procurement solution. Check it out below:

Recent Articles

2025 in review: Milestones, insights and achievements

2025 – a year of that brought meaningful developments for Felix as we continue to address the evolving needs of organisations navigating complex supply-chain environments.

Top 10 reasons for a centralised vendor database

As organisations grow, so does the complexity of managing vendor relationships. Many still rely on spreadsheets or siloed systems, which can lead to inefficiencies, data inconsistencies, and compliance risks. A centralised vendor database offers a smarter, more scalable solution that brings structure, visibility, and control to procurement operations.

Here are the top 10 reasons why centralising your vendor data is a strategic move.

Five ways poor contract storage could be costing your organisation money

Contracts are the backbone of every business relationship – legally binding documents that define expectations, responsibilities, and value.

But what if the way your organisation stores those contracts is quietly costing you money?

Let's stay in touch

Get the monthly dose of supply chain, procurement and technology insights with the Felix newsletter.